They say public speaking is more terrifying than death, paying taxes or baby-sitting all four grandchildren at the same time. However, I'm used to speaking in front of large groups, since I've been doing it for more than 30 years.

I teach a morning class at the local college, where I try to keep 40 post-adolescents awake for an hour and a half so they will learn something about child development.

Over the years, I've talked to rooms full of professors, doctors, women's club members, business professionals, writers, and elderly people who are hard of hearing and miss most of what I say. I've even presented information on TV to millions of viewers across the country.

Yet there is nothing more terrifying than speaking to 120 fourth-graders for 30 minutes.

Why the terror? They're just kids, right? How frightening could they be? Well, if I remember my fourth grade correctly, I spent most of class time writing and passing secret coded messages to my friends behind my teachers' backs instead of paying attention to the lesson.

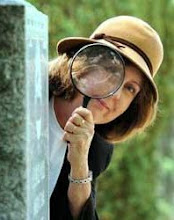

How did this all come about? After writing several mysteries for adults, I decided I wanted to pen a mystery for kids, based on my extensive experience in writing and passing secret codes in fourth grade.I felt I could justify the topic because, as an educator, I knew codes offered benefits beyond just entertainment. They help increase language, math, and cognitive skills, (but please don't tell that to the kids).

So when my book, "The Code Busters Club," came out last week, I gave a copy to my neighbor Connor Brien, a fourth-grader, to see what he thought. Apparently he told his teacher about the book, and soon I had an invitation to come speak to the entire fourth grade at his school.

OMG, as they say in text-messaging code. What would I talk to 120 kids about for 30 long minutes? My exciting writing life? My excellent typing skills? My love of Dr. Seuss books? There wouldn't be an open eye left in the place if I did that -- everyone would be sound asleep.

OK, how about codes? I would supply the kids with "code-busting kits" filled with secret origami-folded message holders, Caesar cipher wheels, invisible ink pens and Morse code whistle/lights, then teach them how to make and break codes. So I quickly whipped up a bunch of code-busting kits and tested my theory on Ms. Vamvouris' fifth-grade class at Greenbrook Elementary School in Danville, with only 30 kids. It went well -- at least, nobody asked if it was time to do math instead.

After making 120 more kits, I was ready to face all those fourth-graders in the Greenbrook School library. Moments later, the four classes filed in, accompanied by their teachers: Ms. Hegarty, Ms. Edgren, Ms. Caldera, Ms. Ravin and Ms. Cowles.

To my surprise, these weren't sleepy-eyed, fidgety students just waiting for the recess bell to ring. They were actually excited to be there and learn how to cracking codes -- everything from Morse to semaphore. Before I knew it, 30 minutes was up. I could have stayed another three or four hours.

I hope they learned something. I certainly did.

Giving 120 fourth-graders whistles for Morse Code was a mistake. When I talk to another fifth-grade class next week, I'll know better...